Over at TIC: Thomas Jefferson, Polar Star

John Betjeman Assesses C.S. Lewis, 1939

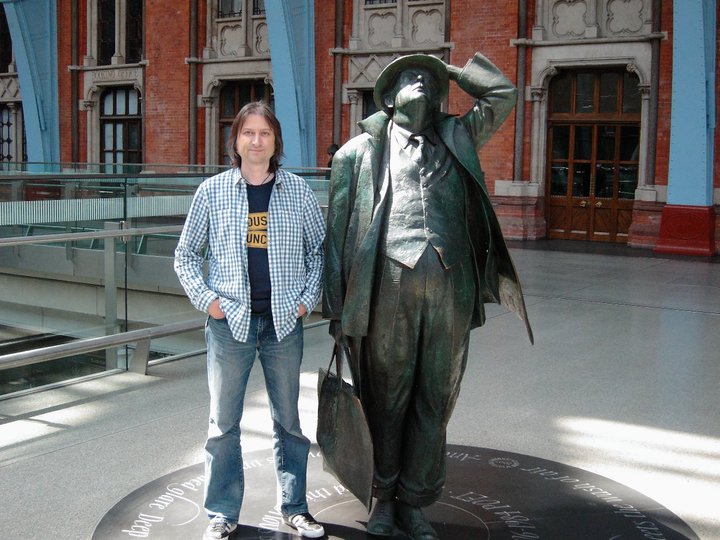

Greg Spawton (who introduced me to the sheer beauty of Betjeman’s through his extraordinary song, “The Permanent Way”) and the famous statue of John Betjeman, a student of both T.S. Eliot and C.S. Lewis.

Source: John Betjeman to C.S. Lewis, December 13, 1939, in Candida Lycett Green, ed., John Betjeman Letters, Vol. 1, pp. 250-253.

Dear Mr Lewis,

Since I have just expunged from the proofs of a preface of a new book of poems of mine which Murray is publishing, a long and unprovoked attack upon you, I wonder whether you will forgive my going into some detail with you personally over the reasons for my attitude? I did not get an opportunity of speaking to you at that dreary Swanwick affair.

You were kind enough to say in a letter to me of about one and a half years ago that you had always regarded ours as a purely literary battle. I must say that it may have become that now, but it started on my side as a rather malicious personal battle. I think it only fair to explain why. When I was finally obliged to leave Magdalen, it was necessary for me to get a job to keep myself because my father had quite rightly washed his hands of me. In order to obtain a post in the inevitable prep school mastering to which all unsuccessful undergraduates of my type are reduced, I needed written testimonials from the President of my college, the headmaster of my school and my tutor. I applied to you for a testimonial and you told me you could not say anything in my favour academically (at tutorials you frequently told me I had ‘no literary style’, and would only get a third and I certainly did little or no work for you as a consequence). So on this testimonial the only thing you said was that I was kindhearted and cheerful. It lost me three decentish jobs before I realised that I would be wiser not to show this testimonial in future so I got another and a good one from my only Magdalen friend, Revd J. M. Thompson! Naturally I was inflamed against you and thought, with the impulsiveness of a young man, that you had done it out of malice from the easy security of an Oxford Senior Common Room. The tragedy of it was heightened by the fact that I have always had a great love for English Literature — and none for philology — and that it was my ambition to become a don and read English Literature to the accompaniment of lovely surroundings. I thought of you as reading philology in surroundings which you did not appreciate. I visualized that white unlived-in room of yours in New Buildings, with the tobacco jars and fixture cards from Philosophy clubs and the green loose covers on the furniture which always depressed me. And when I was working in various far more repulsive surroundings in suburban and industrial England, I often thought of those rooms and envied you a good deal.

It was not until I got on to the subject of your tutorials with Henry Yorke (who, as Henry Green, has written novels which are better than anything I shall ever do) that I found a fellow sufferer and managed to get the whole thing more in perspective.

In those early days I remember you condemning Uncle Tom Eliot to me, and I admired him greatly then, and I still do. In fact you were going to make a parody of his poetry and send it to the Criterion or some such paper. Now I see from Rehabilitations that you take him seriously. It is from signs such as this, that I feel your attitude to poetry, if not to me, will have changed a little, so that you will be willing to attend to my side of the ‘literary’ battle which has emerged from a personal antipathy.

It seems to me that we have two different approaches to poetry. Both, I hope, have a sense of the sound of words and of metre and stress in common. After that there is no common ground. Your approach is philosophical, or metaphysical or abstract or something I do not understand. Mine is visual. The difference of our views comes out clearly in your book on Spenser. Nowhere in that excellent book do you say anything appreciative or discerning of Spenser’s amazing powers of topographical description, which are best appreciated when one has visited the neighbourhood of Clonmel, Waterford and Youghal. Of course, you may rightly reply that that had been done enough already. In that case I would cite a bit of your own poetry — a poem called ‘The Planets’ which opens with the line:

Lady Luna in light canoe.

I don’t see how anyone who has looked at the moon can think of it as

‘cruising monthly’ in a light canoe. I can’t even see that the excuse that this is an experiment only justifies such an opening for a poem given some prominence in your book. If we are going back to the days of my lack of style, what ‘style’ is this if such a thing as ‘style’ exists. It seems to me as out of touch as your talk about Dragons with Tolkien in a Berkshire bar must have seemed to the Berkshire workman. I know something of Berkshire workmen by now! Probably to you, the opening of Tennyson’s ‘Princess’ is just funny, while to me it is moving and good. Probably you prefer the ‘Wreck of the Deutschland’, which I cannot understand, to the ‘Epithalamion’ on p. 89 of the Hopkins book. But there is not object in continuing this speculation. You confessed yourself to me in your kind letter I referred to of one and a half years ago, as not quickened in architectural matters and it seems to bear out my point. For I don’t see how anyone with visual sensibility can live in Magdalen and be unmoved by architecture, if their job is partly that of teaching an appreciation of English literature. A mathematician would certainly be moved, how much more someone who reads English poetry?

I was a very usual type of undergraduate, caught up with the fashions in ‘art’, pretentious and superficial. But all that, I have since discovered, is quite right in this type. Indeed it should be encouraged, for it argues an awareness of what is going on and an incipient sensibility which can easily be crushed or misdirected for ever by an antipathetic tutor. As you said in your letter, ‘I was a very young tutor’.

I would not like you to think I was blaming you for this lack of visual interest, which you would probably be the first to confirm. But if you still lack the sense, I expect you now know when other people have it. And here I am afraid you will think me very rude. When one of the Betjeman type comes to you now for tutorials, are you able to send him on to someone else? I should suggest Nichol Smith or Blunden or old John Bryson or Nevill [Coghill] as suitable tutors. Not a Mr MacFarlane, whom I remember with disgust as making easy game of Dr Johnson for an undergraduate audience. In my day there was no escape.

I feel I have been unpardonably rude in this letter. But the subject is one on which I still feel deeply and this all certainly reads like a heart to hearter from someone who has just joined the Oxford Group movement.

There is just one more thing that itches which I would like to display. When I went in for the English group I had a viva from a Mr. Brett Smith. My answers on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century writers were not, I suspect, bad and Mr B. S. asked me at the viva, ‘Why are you not in for the Honours School?’ You were at the same table with him.

Having now completely explained the causes of my former annoyance, I can put this in the post and sleep contented — for! still sometimes wake up angry in the night and think of the mess I made at Oxford. This letter has taken about two hours to write. I hope you will not give it more than two minutes. It was written largely as a self-vindication and requires no reply, if you do not feel inclined to make one.

Yours sincerely, John Betjeman

The Incomparable Gift of Excellence: Big Big Train’s STONE AND STEEL

Big Big Train, STONE AND STEEL (GEP, 2016), blu-ray; and Big Big Train, FROM STONE AND STEEL (GEP, 2016), download.

The band’s first blu-ray.

The band’s first blu-ray.

Twelve stones from the water. . . .

Yesterday, thanks to the fine folks at Burning Shed, the first blu-ray release from Big Big Train, STONE AND STEEL, arrived safely on American soil. Then, today, thanks to the crazy miracle of the internet, Bandcamp allowed me to download FROM STONE AND STEEL.

In a span of twenty-four hours, my musical world has been thrown into a bit of majestic ecstasy.

2016 might yet be the best year yet to be a fan/devotee/admirer/fanatic (oh, yeah: fan) of the band, Big Big Train. I’ve proudly been a Passenger since Carl Olson first introduced me to the band’s music around 2009. And, admittedly, not just A fan, but, here’s hoping, THE American fan. At least that’s what I wanted…

View original post 1,248 more words

Lizzie strikes again!

When you are shrouded, how does one go? Who am I, that which beget me? Love which holds the universe fastened together, where do I pass and are you mindful? Why, if you are? That such intricacies exist which we do not know: a caterpillar chewing a green leaf, a frog dying in a pond alone, baby chicks hatching in […]

Rachel Gough: Radical Locatedness

Every month, I eagerly await the new piece at KINDRED by my excellent and amazing friend, Rachel W. Gough. My wait is always well worth it. She’s one of my favorite writers as well as one of my favorite persons.

Every month, I eagerly await the new piece at KINDRED by my excellent and amazing friend, Rachel W. Gough. My wait is always well worth it. She’s one of my favorite writers as well as one of my favorite persons.

I CAME ACROSS a striking quote recently: “Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbor is the holiest object presented to your senses.” C.S. Lewis wrote those words in The Weight of Glory, and, no matter one’s religious persuasion, it would be difficult to deny that his statement has zing. What would it look like if we lived as if this were true?

I found this and many other fascinating passages about loving our neighbor as I was preparing for a conversation with my friend Ben Katt of Thresholds. He interviewed me for a podcast on building community in rural neighborhoods, and I dug into the idea of what it means to love your neighbor and invest in place.

To read the full thing (and, as always, you should; Rachel writes nothing that is not important and beautiful), go here.

The Glories of Civic Associations in a Republic

“SERVICE THE ONE GREAT IDEAL”

“SERVICE THE ONE GREAT IDEAL”

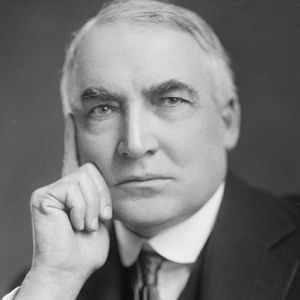

by President Warren G. Harding

[Address before the Rotary International Convention, Coliseum, St. Louis, Mo., June 21, 1923, 4:30 p. m.]

***

Mr. Chairman and Fellow Rotarians:

If I ever make another application for Rotarian membership and a special class cannot be found in which to place me, I am going to propose that they admit me as the chief consumer of films in the United States.

It is a joy to come and greet you. You are not precisely on my schedule; but let me say that if I could plant the spirit of Rotary in every community throughout the

world I would do so, and then I would guarantee the tranquility and the forward march of the world. Statesmen have their problems; governments have theirs; but if we could spread the spirit of Rotary throughout the globe and turn it to practical application, there would not be much wrong with the human procession.

Story of the Blacksmith

I can understand how you have grown and how you have come to exercise a great influence. It is because, fellow Rotarians, no matter whence you come, service is the greatest thing in the world and you are always performing some service, and doing so conscientiously. You are saving America from a sordid existence and putting a little more of soul in the life of this Republic. I do not pretend to say that you are alone in the good work; but I do not wish America ever to be without ideals. I do not want our America to be without some practical conception of service, and then I want that conception put into practice.

Nor do I come to recommend a service that shall be wholly free from compensation. Every service in life worthwhile has its compensation. Some of you, perhaps, have seen what I consider one of the greatest plays, if not the greatest, that was ever written. You may have seen Forbes Robertson, the great English actor, in ‘The Passing of the Third Floor Back.” In that play he became a dweller in a boarding house where the boarders were ill-tempered, irritable, and living at cross purposes, and he brought to that unhappy place the spirit of service. He taught the dissatisfied house servant that after all there was a dignity to the humblest service in the world, and that honesty ought to attend it; he taught the dishonest gambler how honesty would elevate his life; he put an end to the snob, and everywhere, by the preaching of the dignity of and the compensation in service he transformed an unhappy household into one of the happiest and most harmonious.

Nor do I come to recommend a service that shall be wholly free from compensation. Every service in life worthwhile has its compensation. Some of you, perhaps, have seen what I consider one of the greatest plays, if not the greatest, that was ever written. You may have seen Forbes Robertson, the great English actor, in ‘The Passing of the Third Floor Back.” In that play he became a dweller in a boarding house where the boarders were ill-tempered, irritable, and living at cross purposes, and he brought to that unhappy place the spirit of service. He taught the dissatisfied house servant that after all there was a dignity to the humblest service in the world, and that honesty ought to attend it; he taught the dishonest gambler how honesty would elevate his life; he put an end to the snob, and everywhere, by the preaching of the dignity of and the compensation in service he transformed an unhappy household into one of the happiest and most harmonious.

My convictions came from the atmosphere of the small town in which I began my life. In that little town where I ran a newspaper for so many years — I will not recount their number — one day there came a modest little black- smith, who had nothing in the world but genius in his head and courage in his heart. He did not have a dollar of money, but with his genius and his courage he convinced some other men that he could be of service in the upbuilding of that community by the establishment of an industry. He succeeded in establishing it, and it grew until the modest little blacksmith became the outstanding captain of industry in that community. As he served he profited in serving; he aided working men to acquire homes; he relieved the distressed; he offered sympathy. He was the outstanding figure in a community of twenty or twenty-five thousand people, and one day when, all too soon, his career of service came to an end, every activity in that community wasstopped, and everybody halted to do reverence to the memory of a man who had come to the village to serve and to make it and his fellows better.

Put Ideals Into Practice

I can give you a more striking example than that, however. In a town in Ohio some years ago, there lived a veteran of the Civil War, whose heroism and whose capacity combined to make him a brigadier general in the war for the Union; but he, unfortunately, had his public career marred prior to the war without any fault on his part, and so he was obliged to forego public life for which he was eminently fitted. However, he gave of his eloquent tongue, unmatched in America, to service, and he gave of his great big heart to service, and he gave of his practical mind to service, so that he became the greatest contributor to the community in which he resided. One day when he came to his end, after ripened years, not only did the whole community stop to mourn him, but every tear that was dropped upon the bier of General W. H. Gibson reflected the rainbow that spanned the arch between reverence and affection. There was paid to this humble man of service the greatest tribute that community life may pay.

Oh, fellow Rotarians, your service is not alone in developing your ideals; it is in putting your ideals into practice. What the world needs today more than anything else is to understand that service alone will bring about restoration after the tumult of the World War. If we can all get down to service, ample service, honest service, helpful service, and appreciate the things that humanity must do to insure recovery, then there will come out of the great despondency and discouragement and distress of the world a new order; and someday I fancy I shall see the emblem of Rotary in the foreground, because you of Rotary, representative of the best we have in America, have played your big part in making service one of the appraised worthwhile offerings of humankind.

The Truth about Ronald Reagan

Nearly three decades after the Reagan administration ended, several views of the fortieth president—all conflicting—have taken hold in the American popular mind. The post The Truth about Ronald Reagan appeared first on The Imaginative Conservative.

http://www.theimaginativeconservative.org/2016/04/truth-about-ronald-reagan.html

Colin Hardie’s Obit of C.S. Lewis

C.S. Lewis, 1898-1963

The last sentence of your obituary may give the impression that C.S. Lewis was too busy writing to have much time for social relations, and that he had little gift for them. To many this will seem much less than the truth. He spoke his mind and loved an argument, but was always fair and unfailingly courteous. When children wrote to him about his Narnia books, they always and at once received a delightfully personal reply, no mere stock acknowledgement. With his colleagues at Magdalen or Magdalene he did not casually get on Christian-name terms, but he had, in an older more formal tradition, an exacting standard of consideration for a colleague as such, whether he liked him or not. In a college meeting he could appear brusque, when he put one devastating point with absolute clarity, and, no doubt. a tutorial with him could be a purgation, without fear or favour, but without animus. With his friends he was a brilliant conversationalist, full of wit and humour and the apt anecdote or image. They were a varied, almost heterogeneous, company, held together by affection and admiration for him. His heavy build and stout red, not very expressive, face made him formidable to some, much more than he ever realized, and in some ways belied the inner mind and the grace and courtesy of his intention, but also expressed his firmness of conviction and an integrity without illusion or pretence. His inner-eye and ear moved in a world of entrancing beauty and music, but his rooms at home or in college were dowdy and comfortable (not very), like his clothes; and he read the poetry of the many foreign languages he knew in a very British way.

–C.G.H. [Colin G. Hardie, an Inkling], “Prof. C.S. Lewis,” London Times (November 28, 1963), 18.

Albert Jay Nock, 20th-Century DemiGod

Albert Jay Nock, 1870-1945

There are a number of writers who both inspire and humble me. Albert Jay Nock, perhaps the most individual of individualists, almost always floors me when I read him. He enlivens my soul and my mind, but he especially inspires me to be a better man. He, himself, was nothing if not a man of absolute integrity.

Thanks to Daniel McCarthy, I’ve been re-reading Albert Jay Nock like mad. The more I read of him, the more I love him. Happily, I’ve been reading him since college, but it was brilliant Walter Grinder who first made me realize just how great a man Nock was.

If Nock’s remembered, it’s generally for his anti-New Deal book, Our Enemy, The State (1935), but really, this is probably not his best book. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a truly fine book and, certainly, he’s not incorrect in his assessment of that wretched FDR, but because Nock is simply too angry when he’s writing it.

His other books are deeply genteel and liberal (in the sense of the liberal arts). Like so many of us, Nock is best when he writes about what he loves rather than what he despises.

Thankfully, I’m not unique in loving Nock and his writing.

Here are the folks from the past who claimed to adore Nock and, to one degree or another, were inspired by him. Not just inspired, but so inspired as to become better writers (of a certain type) and better thinkers because of his example.

- Rose Wilder Lane

- Isabel Paterson

- Henry Regnery

- Bernard Iddings Bell

- Russell Kirk

- William F. Buckley

- Frank Chodorov

- Suzanne LaFollette

- Robert Nisbet

Nisbet had actually read Nock’s MEMOIRS so many times that he’d memorized it!

Others?

It’s rather clear, he is the single most important nexus between pre-WWII non-leftist thought and all modern conservatism and libertarianism.

Much more to come. . . .

My Favorite Anti-Federalist Papers

Federal Farmer 1

Federal Farmer 1

http://www.constitution.org/afp/fedfar01.htm

Federal Farmer 2

http://www.constitution.org/afp/fedfar03.htm

Federal Farmer 16

http://www.constitution.org/afp/fedfar16.htm

Old Whig 1

http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/an-old-whig-i/

Old Whig 3

http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/an-old-whig-iii/

Brutus 1

http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/brutus-i/

Brutus 8

http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/brutus-viii/

Why Robert Nisbet Matters

I had a blast writing this article about one of my favorite thinkers, Robert Nisbet, for The American Conservative.

I had a blast writing this article about one of my favorite thinkers, Robert Nisbet, for The American Conservative.Lehner’s Catholic Enlightenment

2016.

This morning at The Imaginative Conservative, my review of an extraordinary new book by Ulrich Lehner.

The sum of Dr. Lehner’s argument is this: contrary to popular and secular mythologies, the Church possessed a number of critical personalities and intellectual leaders who actively engaged the ideas of democracy, individualism, liberalism (properly understood), and what would be called, ultimately, modernity. All of this happened between the Council of Trent and the end of the French Revolution. Surprisingly, at least to me, Catholic scholars and theologians considered, studied, and digested the importance of the thought of John Locke, Immanuel Kant, and even Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Indeed, they not only took the ideas of non-Catholic scholars seriously, they actually attempted to meld secular thought with Catholic theology. Dr. Lehner, much to his credit, never over-makes his case. He recognizes that there were many, many “Enlightenments” during the few centuries leading up to the French Revolution, just as our own John Willson stresses the need to acknowledge many “Foundings” in the American Founding period. Additionally, Dr. Lehner never claims that these Catholic Enlighteners—as he calls them—dominated scholarship or the thinking of the Church as a whole. Rather, he notes, time and time again throughout his book, they attracted attention, bonded with one another, and changed, shaped, and delimited the philosophical and theological discussion within the Church.