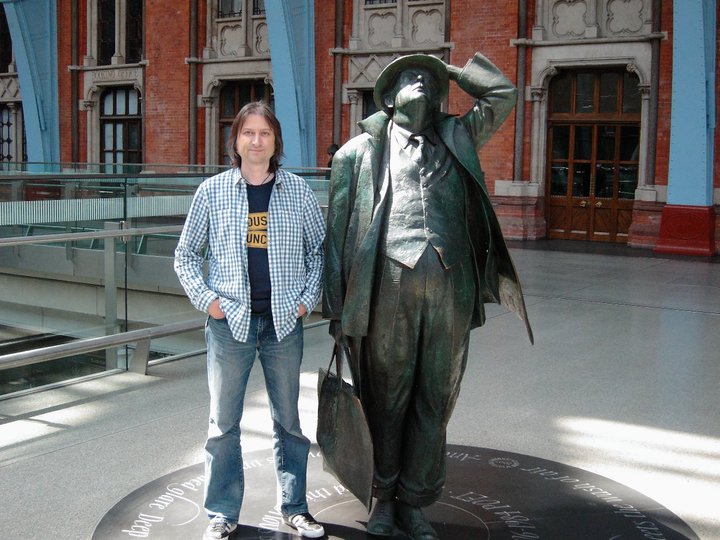

Greg Spawton (who introduced me to the sheer beauty of Betjeman’s through his extraordinary song, “The Permanent Way”) and the famous statue of John Betjeman, a student of both T.S. Eliot and C.S. Lewis.

Source: John Betjeman to C.S. Lewis, December 13, 1939, in Candida Lycett Green, ed., John Betjeman Letters, Vol. 1, pp. 250-253.

Dear Mr Lewis,

Since I have just expunged from the proofs of a preface of a new book of poems of mine which Murray is publishing, a long and unprovoked attack upon you, I wonder whether you will forgive my going into some detail with you personally over the reasons for my attitude? I did not get an opportunity of speaking to you at that dreary Swanwick affair.

You were kind enough to say in a letter to me of about one and a half years ago that you had always regarded ours as a purely literary battle. I must say that it may have become that now, but it started on my side as a rather malicious personal battle. I think it only fair to explain why. When I was finally obliged to leave Magdalen, it was necessary for me to get a job to keep myself because my father had quite rightly washed his hands of me. In order to obtain a post in the inevitable prep school mastering to which all unsuccessful undergraduates of my type are reduced, I needed written testimonials from the President of my college, the headmaster of my school and my tutor. I applied to you for a testimonial and you told me you could not say anything in my favour academically (at tutorials you frequently told me I had ‘no literary style’, and would only get a third and I certainly did little or no work for you as a consequence). So on this testimonial the only thing you said was that I was kindhearted and cheerful. It lost me three decentish jobs before I realised that I would be wiser not to show this testimonial in future so I got another and a good one from my only Magdalen friend, Revd J. M. Thompson! Naturally I was inflamed against you and thought, with the impulsiveness of a young man, that you had done it out of malice from the easy security of an Oxford Senior Common Room. The tragedy of it was heightened by the fact that I have always had a great love for English Literature — and none for philology — and that it was my ambition to become a don and read English Literature to the accompaniment of lovely surroundings. I thought of you as reading philology in surroundings which you did not appreciate. I visualized that white unlived-in room of yours in New Buildings, with the tobacco jars and fixture cards from Philosophy clubs and the green loose covers on the furniture which always depressed me. And when I was working in various far more repulsive surroundings in suburban and industrial England, I often thought of those rooms and envied you a good deal.

It was not until I got on to the subject of your tutorials with Henry Yorke (who, as Henry Green, has written novels which are better than anything I shall ever do) that I found a fellow sufferer and managed to get the whole thing more in perspective.

In those early days I remember you condemning Uncle Tom Eliot to me, and I admired him greatly then, and I still do. In fact you were going to make a parody of his poetry and send it to the Criterion or some such paper. Now I see from Rehabilitations that you take him seriously. It is from signs such as this, that I feel your attitude to poetry, if not to me, will have changed a little, so that you will be willing to attend to my side of the ‘literary’ battle which has emerged from a personal antipathy.

It seems to me that we have two different approaches to poetry. Both, I hope, have a sense of the sound of words and of metre and stress in common. After that there is no common ground. Your approach is philosophical, or metaphysical or abstract or something I do not understand. Mine is visual. The difference of our views comes out clearly in your book on Spenser. Nowhere in that excellent book do you say anything appreciative or discerning of Spenser’s amazing powers of topographical description, which are best appreciated when one has visited the neighbourhood of Clonmel, Waterford and Youghal. Of course, you may rightly reply that that had been done enough already. In that case I would cite a bit of your own poetry — a poem called ‘The Planets’ which opens with the line:

Lady Luna in light canoe.

I don’t see how anyone who has looked at the moon can think of it as

‘cruising monthly’ in a light canoe. I can’t even see that the excuse that this is an experiment only justifies such an opening for a poem given some prominence in your book. If we are going back to the days of my lack of style, what ‘style’ is this if such a thing as ‘style’ exists. It seems to me as out of touch as your talk about Dragons with Tolkien in a Berkshire bar must have seemed to the Berkshire workman. I know something of Berkshire workmen by now! Probably to you, the opening of Tennyson’s ‘Princess’ is just funny, while to me it is moving and good. Probably you prefer the ‘Wreck of the Deutschland’, which I cannot understand, to the ‘Epithalamion’ on p. 89 of the Hopkins book. But there is not object in continuing this speculation. You confessed yourself to me in your kind letter I referred to of one and a half years ago, as not quickened in architectural matters and it seems to bear out my point. For I don’t see how anyone with visual sensibility can live in Magdalen and be unmoved by architecture, if their job is partly that of teaching an appreciation of English literature. A mathematician would certainly be moved, how much more someone who reads English poetry?

I was a very usual type of undergraduate, caught up with the fashions in ‘art’, pretentious and superficial. But all that, I have since discovered, is quite right in this type. Indeed it should be encouraged, for it argues an awareness of what is going on and an incipient sensibility which can easily be crushed or misdirected for ever by an antipathetic tutor. As you said in your letter, ‘I was a very young tutor’.

I would not like you to think I was blaming you for this lack of visual interest, which you would probably be the first to confirm. But if you still lack the sense, I expect you now know when other people have it. And here I am afraid you will think me very rude. When one of the Betjeman type comes to you now for tutorials, are you able to send him on to someone else? I should suggest Nichol Smith or Blunden or old John Bryson or Nevill [Coghill] as suitable tutors. Not a Mr MacFarlane, whom I remember with disgust as making easy game of Dr Johnson for an undergraduate audience. In my day there was no escape.

I feel I have been unpardonably rude in this letter. But the subject is one on which I still feel deeply and this all certainly reads like a heart to hearter from someone who has just joined the Oxford Group movement.

There is just one more thing that itches which I would like to display. When I went in for the English group I had a viva from a Mr. Brett Smith. My answers on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century writers were not, I suspect, bad and Mr B. S. asked me at the viva, ‘Why are you not in for the Honours School?’ You were at the same table with him.

Having now completely explained the causes of my former annoyance, I can put this in the post and sleep contented — for! still sometimes wake up angry in the night and think of the mess I made at Oxford. This letter has taken about two hours to write. I hope you will not give it more than two minutes. It was written largely as a self-vindication and requires no reply, if you do not feel inclined to make one.

Yours sincerely, John Betjeman