Interim President and CEO of THE AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE

Dear Friends,

Dear Friends,

I am extremely honored to announce that I have been named the interim President and CEO of The American Conservative magazine and its parent NPO. It is interim—a one-year position as steward (Faramir) as we search for the return of the king (Aragorn).*

My position with TAC will, in no way, affect my day-to-day duties (or loyalties) to Hillsdale College or The Imaginative Conservative.

Indeed, it is clearly Winston Elliott and his magisterial The Imaginative Conservative and the experience and opportunities it has offered me that paved the way toward the interim position with TAC. TIC-TAC! Ave, Winston.

And, of course, a huge thanks to my great friends, Dan McCarthy, Mark Kalthoff, and Tom Woods, for their encouragement. And, to Sarah Skwire and Steve Horwitz, too. Oh yeah—that mighty Johnny Burtka as well!

As it always has, The American Conservative seeks and will continue to seek “ideas over ideology” and “principles over party.”

Yours, delightedly, Brad

*This makes Dedra, Eowyn. Makes perfect sense.

The Failure of American History Textbooks

What are the good American history textbooks out there?

What are the good American history textbooks out there?

The best one, by George Tindall and David Shi, declines in quality (but not quantity!) with every new edition. Here’s a telling example. The text, America: A Narrative History (brief 9th ed.), gives the impression that Maryland was somehow a semi-tolerant Catholic colony.

This is demonstrably untrue after 1689.

Beginning with the so-called “Coup of 1689” and the full repeal of the Toleration Act of 1649, Maryland instituted the strongest and most effective anti-Catholic laws in the North American colonies. A practicing Catholic:

- Couldn’t vote

- Couldn’t hold office

- Couldn’t bear witness/testify in a court of law

- Couldn’t practice law

- Had to practice his religion, ultimately, in a private chapel

- Had his land double (and sometimes more) taxed; additionally, his land was always liable to confiscation during times of war, especially if against Catholics

- Often could not raise a child in the “Catholic fashion” without having the child forcibly removed from the Catholic parent(s) and shipped to England to live with a Protestant family.

The end of such laws also reveal the power of the American Revolution, for the extra legal associations of 1774 swept aside these laws, even as the First Continental Congress condemned the Quebec Act on October 21, 1774, viewing the act as a “power, to reduce the ancient, free Protestant colonies to . . . slavery. . . Nor can we suppress our astonishment that a British parliament should ever consent to establish in that country a religion that has deluged your island with blood, and dispersed impiety, bigotry, persecution, murder and rebellion through every part of the world.”

What a world.

True Educational Reform

Dorothy Sayers contemplating the last things.

[From a few years ago. . .]

As I had mentioned in a previous post, I’m heading to Indianapolis this weekend for a conference on the meaning of liberty and education. One of the finest books I’ve come across in preparation for this colloquium is Liberty Funds on 1973 book, Education in a Free Society. The book concludes with Dorothy Sayers classic piece, “The Lost Tools of Learning.” Originally written at the beginning of the Cold War and delivered at Oxford, Sayers’s piece has as much to tell us now—if not more–than it did in the 1940s.

As Sayers believes it, western civilization was in slow decline, in large part, because it relied so heavily on the educational inheritance of previous generations. But, it was using up that inheritance as quickly as possible, approaching the point of its complete disintegration.

“Many people today who were atheist or agnostic and religion, are governed in their conduct by a code of Christian ethics which is so rooted in their unconscious assumptions that it never occurs to them to question it. But one cannot live on capital for ever. A tradition, however firmly rooted, if it is never watered, though it dies hard, yet in the end it dies.”

Like other Christian humanist critics of the time, especially Albert Jay Nock, Romano Guardini, and Christopher Dawson, Sayers worried that with the declining importance of the liberal arts, not only would education become compartmentalized into a variety of “subjects,” but that those educated in such a system would take their own subjective preferences into society itself. Consequently, a man might know much—that is, he might know an outrageous number of facts—about a thing, but he would be unable to place that thing into a larger and important context. In other words, he would prefer the particular to the universal, perhaps not even knowing a universal existed. One might consider this educated man incredibly knowledgeable, but no one would mistake him for being wise.

The Genius of Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (1478-1535)

Sir Thomas More (1478-1535)

An argument could be made that the world ended when Henry VIII had Thomas More executed. Or, perhaps, in less drastic terms, the “modern world” began on July 6, 1535. What was left of the world of Christendom faded away at that moment. This argument actually seems more plausible than the claim that some historians have made that the modern world began with Luther and Calvin. In almost every way, Luther and Calvin–with More, John Fisher, and Erasmus–looked first and foremost to the past for guidance and inspiration. Luther was a devout Augustinian, and Calvin’s first love was the Stoicism of Seneca.

A few glimpses into More’s personal correspondence reveal much about his innocence and hope.

“For His wisdom better sees what is good for us than we do ourselves. Therefore, I pray you be of good cheer, and take all the household with you to church, and there thank God both for that He hath given us and for that He hath taken away from us, and for that He hath left us, which, if it please Him, He can increase when He will. And if it please Him to leave us yet, as His pleasure be it.” (Thomas More to Mistress Alice, September 3, 1529, in Steve Smith, ed., For All Seasons, letter 51)

“The more I realize that this post involves the interests of Christendom, my dearest Erasmus, the more I hope it all turns out successfully.” (Thomas More to Erasmus, October 29, 1529, in Steve Smith, ed., For All Seasons, letter 53)

“Congratulations, then, my dear Erasmus, on your outstanding virtuous qualities; however, if on occasion some good person is unsettled and disturbed by some point, even without a sufficiently serious reason, still do not be chagrined at making accommodations for the pious dispositions of such men. But as for those snapping, growling, malicious fellows, ignore them and, without faltering, quietly continue to devote your self to the promotion of intellectual things and the advancement of virtue.” (Thomas More to Erasmus, June 14, 1532, in Steve Smith, ed., For All Seasons, letter 54)

Paul Rahe’s De Tocqueville

From a response, “Republican Virtue, Democratic Spirit,” delivered on April 7, 2009, at Hillsdale College to Paul Rahe’s excellent work on Alexis De Tocqueville.

From a response, “Republican Virtue, Democratic Spirit,” delivered on April 7, 2009, at Hillsdale College to Paul Rahe’s excellent work on Alexis De Tocqueville.

Thank you, Professor Schlueter for organizing this and for inviting me to speak. Thank you, Miss Essley, for your kind introduction.

Professor Paul Rahe [professor of history and political science, Hillsdale College] is not a happy man. Nor should he be. From almost any perspective, the state of the world appears rather bleak.

Everywhere, we see an economy in tatters, a people uncertain, and a culture corrupted, perhaps beyond redemption. Perhaps. Stimulus packages, plans to add untold debt as a burden upon our children and grandchildren, and promises from the Federal Reserve to print money all should give us pause.

More immediate dangers exist. Across the Pacific, a missile was launched this weekend from a regime we should have eradicated in the early 1950s. We are now living with our previous errors in judgment.

To put it simply (and perhaps a bit “simplistically”—but I prefer to think of it as putting it “with fervor”), Christopher Dawson was one of the greatest historians of the twentieth century, certainly one of its greatest men of letters, and perhaps one of the most respected Catholic scholars in the English speaking world. I’ve have had the opportunity and privilege to argue this elsewhere, including here at the majestic The Imaginative Conservative. I would even go so far as to claim that Dawson was THE historian of the past 100 years.

To put it simply (and perhaps a bit “simplistically”—but I prefer to think of it as putting it “with fervor”), Christopher Dawson was one of the greatest historians of the twentieth century, certainly one of its greatest men of letters, and perhaps one of the most respected Catholic scholars in the English speaking world. I’ve have had the opportunity and privilege to argue this elsewhere, including here at the majestic The Imaginative Conservative. I would even go so far as to claim that Dawson was THE historian of the past 100 years.

Without going deeply into Dawson’s thought—or any aspect of it—in this post, it is worthwhile cataloguing how many of his contemporaries claimed him important and his scholarship and ideas for their own. This means, consequently, that while most Americans—Catholic or otherwise—no longer remember Christopher Dawson, they do often remember affectionately those he profoundly (one might even state indelibly) influenced. The list includes well known personalities such as T.S. Eliot, Thomas Merton, J.R.R. Tolkien, and C.S. Lewis.

An Important Note to Readers of Stormfields

Dear Stormfields readers,

First, thank you!

Second, for some reason beyond my control, WordPress erased almost 5,000 of you from my subscriber/followers list. This happened to me about 2 weeks ago at this account and also at my music website, progarchy.

I have no idea why.

Just please know that if you were taken off the subscriber/follower list, it was NOT personal!

Third, if you’d like to sign up again, I’d be more than happy to have you! Let’s hope it’s permanent this time.

Thank you for understanding,

Brad

St. Augustine’s Two Cities: Then and Now

“Nature makes nothing in vain,” Aristotle, the great Pagan philosopher of ancient Athens, understood. Aquinas concluded Aristotle’s argument fourteen centuries later with “only Grace perfects nature.” Following St. Paul’s letters in the New Testament, St. Augustine, eight centuries before Aquinas and seven centuries after Aristotle, wrote: “All natures, then, inasmuch as they are, and have therefore a rank and species of their own, and a kind of internal harmony, are certainly good. And when they are in the places assigned to them by the order of their nature, they preserve such being as they have received.”[1] Nothing could sum up the argument of the Christian Humanists better than the arguments of these three men, one pagan and two Christians: Aristotle, St. Augustine, and St. Aquinas. Everything has its place, its role, its purpose, singular to it, known and understood only fully by the Divine Author, who placed each person and thing in His story, what a monk at the Anglo-Saxon monastery at Lindesfarne called “God’s Spell,” or the Gospel, in 950. The story in which we as human persons participate began with Creation, reached its middle and highest point with the Incarnation, the Death, and the Resurrection of Christ Jesus, and will end with the Apocalypse. The end will come when it comes. Even Jesus claimed not to know His Father’s mind and desires on the subject. Each of us, then, as members of the story, has our role. Some roles are greater, some are lesser, but each has an intrinsic importance. We may neglect our role, we may pervert our gifts, or we may freely give up our free will, through Grace, and submit to God’s Will. St. Augustine challenged his readers:

“Nature makes nothing in vain,” Aristotle, the great Pagan philosopher of ancient Athens, understood. Aquinas concluded Aristotle’s argument fourteen centuries later with “only Grace perfects nature.” Following St. Paul’s letters in the New Testament, St. Augustine, eight centuries before Aquinas and seven centuries after Aristotle, wrote: “All natures, then, inasmuch as they are, and have therefore a rank and species of their own, and a kind of internal harmony, are certainly good. And when they are in the places assigned to them by the order of their nature, they preserve such being as they have received.”[1] Nothing could sum up the argument of the Christian Humanists better than the arguments of these three men, one pagan and two Christians: Aristotle, St. Augustine, and St. Aquinas. Everything has its place, its role, its purpose, singular to it, known and understood only fully by the Divine Author, who placed each person and thing in His story, what a monk at the Anglo-Saxon monastery at Lindesfarne called “God’s Spell,” or the Gospel, in 950. The story in which we as human persons participate began with Creation, reached its middle and highest point with the Incarnation, the Death, and the Resurrection of Christ Jesus, and will end with the Apocalypse. The end will come when it comes. Even Jesus claimed not to know His Father’s mind and desires on the subject. Each of us, then, as members of the story, has our role. Some roles are greater, some are lesser, but each has an intrinsic importance. We may neglect our role, we may pervert our gifts, or we may freely give up our free will, through Grace, and submit to God’s Will. St. Augustine challenged his readers:

Choose now what you will pursue, that your praise may be not in yourself, but in the true God, in whom there is no error. For of popular glory you have had your share; but by the secret providence of God, the true religion was not offered to your choice. Awake, it is now day; as you have already awaked in the persons of some in whose perfect virtue and sufferings for the true faith we glory: for they, contending on all sides with hostile powers, and conquering them all by bravely dying, have purchased for us this country of ours with their blood; to which country we invite you, and exhort you to add yourselves to the number of citizens of this city.[2]

Man Will Never Dominate Nature

In this world, the possibility of exploitation will become most violent when men not only deny God but attempt to dominate nature. C.S. Lewis explored the possibilities of men dominating nature during World War in both realistic and fictional media. “The final stage is come when Man by eugenics, by pre-natal conditioning, and by an education and propaganda based on a perfect applied psychology, has obtained full control over himself,” Lewis explained in The Abolition of Man.[1] Ironically, because this means that the generation that discovers this will overturn all previous generations and shape all future generations, this revolutionary generation will be a tyrant and dehumanize all. “They have stepped into the void,” Lewis argued. “They are not men at all: they are artefacts. Man’s final conquest has proved to be the abolition of Man.”[2] Lewis took the argument to its logical conclusion:

In this world, the possibility of exploitation will become most violent when men not only deny God but attempt to dominate nature. C.S. Lewis explored the possibilities of men dominating nature during World War in both realistic and fictional media. “The final stage is come when Man by eugenics, by pre-natal conditioning, and by an education and propaganda based on a perfect applied psychology, has obtained full control over himself,” Lewis explained in The Abolition of Man.[1] Ironically, because this means that the generation that discovers this will overturn all previous generations and shape all future generations, this revolutionary generation will be a tyrant and dehumanize all. “They have stepped into the void,” Lewis argued. “They are not men at all: they are artefacts. Man’s final conquest has proved to be the abolition of Man.”[2] Lewis took the argument to its logical conclusion:

From the point of view which is accepted in Hell, the whole history of our Earth had led up to this moment. There was now at least a real chance for fallen man to shake off that limitation of his powers which mercy had imposed upon him as a protection from the full results of his fall. If this succeeded, Hell would be at last incarnate. Bad men, while still in the body, still crawling on this little globe, would enter that state which, heretofore, they had entered only after death, would have the diuturnity and power of evil spirits. Nature, all over the globe of Tellus, would become their slave; and of that dominion no end, before the end of time itself, could be certainly foreseen.[3]

Though written in fantastic terms, Lewis’s words from That Hideous Strength ring with truth, and Hell is the winner. Dawson agreed: the machine will become “the blind instrument of a demonic will to power.”[4] With such a victor, Romano Guardini warned, “unspeakable rape of the individual, of the group, even of the whole nation” will be the result, as the terror regimes of the twentieth-century have well demonstrated.[5] Indeed, in modernity, Etienne Gilson realized, knowledge itself is synonymous with destruction.[6]

Barbarians at the Gate

Cycles of Republics

At midnight, August 24, 410, Alaric and his Gothic warriors entered the gates of Rome and sacked the city, pillaging, raping, and murdering for nearly three solid days. Far from considering himself as a ruthless invader of Rome, Alaric viewed himself as a loyal Roman citizen as he entered the Eternal City. He and his men desired formal recognition as legitimate Roman armed forces through titles and pensions.[1] Though the empire had been crumbling for years due to cultural, political, and economic decadence, the event stunned and shattered the western world. And, whatever Alaric’s intentions on August 24th, his army degenerated quickly into a ravaging mob.[2] “When the brightest light on the whole earth was extinguished, when the Roman empire was deprived of its head and when, to speak more correctly, the whole world perished in one city,” wrote St. Jerome, expressing the common sentiment, “I was dumb with silence, I held my peace, even from good, and my sorrow was stirred.”[3] Such an event had seemed inconceivable to those living under the declining protection of the Roman empire. And, yet, it had happened. The great symbol of the vast Roman empire, though no longer the capitol, had fallen to invasion. True, many Christians and their Basilicas were spared, but the city had fallen nonetheless.[4] The ruin continued, St. Jerome lamented.

For twenty years and more Roman blood has been flowing ceaselessly over the broad countries between Constantinople and the Julian Alps where the Goths, the Huns and the Vandals spread ruin and death… How many Roman nobles have been their prey! How many matrons and maidens have fallen victim to their lust! Bishops live in prison, priests and clerics fall by the sword, churches are plundered, Christ’s altars are turned into feeding-troughs, the remains of the martyrs are thrown out of their coffins. On every side sorrow, on every side lamentation, everywhere the image of death.[5]

Though also reeling from the onslaught of the Barbarians, St. Augustine stood firm in his opposition to the pagans and their challenge that Rome fell because it ignored the old gods. Gracefully, he turned the evil of destruction of the barbarians into the creative good of the Church. His defense came in the form of one of the greatest works of Christianity, The City of God (413-426). It would be difficult to exaggerate the importance of this work, as it became the theological, social, cultural, and political handbook, along with scripture, for the middle ages.[6] Through the writing of the City of God, he also importantly came to realize that though Rome may have fallen, Christianity stood strong. “Though he was a loyal Roman and a scholar who realized the value of Greek thought, he regarded these things as temporary and accidental,” Christopher Dawson explained. “He lived not by the light of Athens and Alexandria, but by a new light that had suddenly dawned on the world from the East only a few centuries earlier.”[7] Rome represented the City of Man, in its paganism, decadence, and torture of Christians; Jerusalem represented the City of God.[8] For St. Augustine, one could not readily separate the two cities, the City of God and the City of Man, in any strict dualism or profound opposition. “In truth,” St. Augustine wrote, “these two cities are entangled together in this world, and intermixed until the last judgment effect their separation.”[9] The world experienced two types of time: the cyclical time of the City of Man, and the purposeful time of the City of God, a group of pilgrims making their way through this time, but not of this time.

As with St. Augustine, the Christian Humanists of the twentieth-century looked out over a ruined world: a world on one side controlled by ideologues, and, consequently, a world of the Gulag, the Holocaust camps, the killing fields, and total war; on the other: a world of the pleasures of the flesh, Ad-Men, and the democratic conditioners to be found, especially, in bureaucracies and institutions of education. Both east and west had become dogmatically materialist, though in radically different fashions. In almost all ways, the devastation of Kirk’s and Dawson’s twentieth-century world was far greater than that of St. Augustine’s fifth-century world. At least barbarian man believed in something greater than himself. One could confront him as a man, a man who knew who he was and what he believed, however false that belief might be. But, modern man accepted only ideologies, the false and substitute religions of modernity.

Fifteen centuries after St. Augustine, the barbarians were at the gates.

Notes

[1] Warren Thomas Smith, Augustine: His Life and Thought (Atlanta, Georgia: John Knox Press, 1980), 145.

[2] J.B. Bury, The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians (New York: W.W. Norton, 1967), 96.

[3]St. Jerome quoted in Daniel Boorstin, The Creators, 59

[4] Smith, Augustine, 145-47.

[5] Quoted in Dawson, Enquiries into Religion and Culture, 221.

[6] Dawson, Religion and the Rise of Western Culture, 68; and Dawson, Enquiries into Religion and Culture, 199.

[7] Dawson, “The Hour of Darkness,” The Tablet (December 2 1939), 625.

[8] Dawson, “The Hour of Darkness,” 625.

[9]St. Augustine, The City of God, Book 1, Section 35.

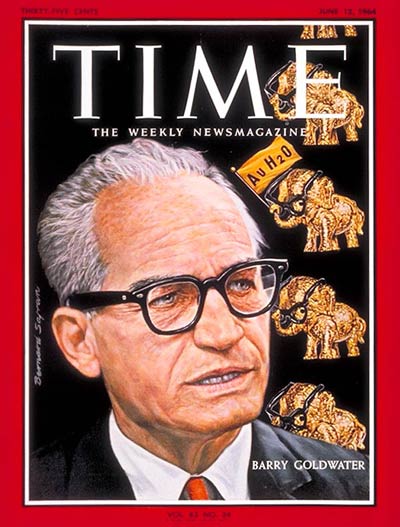

Though Russell Kirk only wrote two speeches for Senator Barry Goldwater, they were very, very good speeches.

Though Russell Kirk only wrote two speeches for Senator Barry Goldwater, they were very, very good speeches.