The Catholic Imagination of Roland Orzabal: Tears for Raoul

Review retrospective: Tears for Fears, RAOUL AND THE KINGS OF SPAIN (Sony, 1995; Cherry Red, 2009).

Twenty years ago, Roland Orzabal (born Raoul Jaime Orzabal de la Quintana to an English mother and a Basque/Spanish/French father) released the fifth Tears for Fears studio album, RAOUL AND THE KINGS OF SPAIN.

Overall, we should remember, 1995 was a pretty amazing year for music—really the year that saw the full birthing of third-wave prog.

Not all was prog, of course, but there was so much that was simply interesting. Natalie Merchant, TIGERLILY; Radiohead, THE BENDS; Spock’s Beard, THE LIGHT; The Flower Kings, BACK IN THE WORLD OF ADVENTURES; Marillion, AFRAID OF SUNLIGHT; and Porcupine Tree, THE SKY MOVES SIDEWAYS.

As the time that RAOUL came out, I liked it quite a bit, but I didn’t love it. The first five songs just floored me, but then I thought the…

View original post 946 more words

Friendship and Art at its Highest: Tears for Fears in Denver, 2015

Last night, my wife and I—just about to celebrate our 17th wedding anniversary—treated ourselves to a concert by Tears for Fears.

For those of you who read progarchy.com regularly, you know that not only do we as a website love the work of TFF, but I, Brad, have been rather obsessed with Roland Orzabal and Curt Smith since 1985.

Yes, 30 years—just four more years than I’ve been in love with Rush. And, of course, what a comparison. Can you imagine Peart and Orzabal writing lyrics together? Tom Sawyer meets Admiral Halsey!

A blurry iPhone picture from last night’s concert in Denver: Tears for Fears.

A blurry iPhone picture from last night’s concert in Denver: Tears for Fears.

I came to TFF in the same way almost every American my age did, from hearing “Everybody wants to rule the world” on MTV. What a glorious song. Here was New Wave, but New Wave-pop-prog. Here were intelligent lyrics. Here, to my mind, was…

View original post 1,378 more words

Grace Perfecting Nature: A Tenth Anniversary Toast to Kate Bush’s “An Endless Sky of Honey”

Most proggers regard side two of Hounds of Love as Kate Bush’s greatest work. I love it as well, and I have since I first heard it thirty years ago this coming autumn. Who wouldn’t be moved by the invocation of Tennyson’s Ninth Wave, by Kate as an ice witch, and by the observation of it all from orbit? The entire album, but especially side two, is a thing of beauty.

A vision of the Natural Law itself: Kate Bush, ca. 2005

A vision of the Natural Law itself: Kate Bush, ca. 2005

Equally gorgeous to me, though, is Bush’s 2005 album, Aerial, and, in particular, side two, “An Endless Sky of Honey.”

No one, no one is here

No one, no one is here

We stand in the Atlantic

We become panoramic

The stars are caught in our hair

The stars are on our fingers

A veil of diamond dust

Just reach up and touch it

The sky’s above…

View original post 474 more words

Rocket 88 Books: Humor and Excellence

Last night, as I was getting ever closer to sleep, I decided to check out the website for Rocket 88 Books.

I’ve been reading and throughly enjoying their book on the history of Dream Theater, LIFTING SHADOWS.

Lo and behold, what did I find on the website? That Rocket 88 will soon be releasing a paperback version of the 2012 coffee-table book, THE SPIRIT OF TALK TALK.

For those of you who know me, you know how much I adore Talk Talk. But, even with my normal lack of frugality and my love of the band, I just couldn’t bring myself to pay the price that was being asked for that hardback–no matter how beautiful–three years ago.

And yet, here it is.

So, of course, I ordered it. Immediately. Here’s the response I awoke to from the press:

Hello Bradley,

Congratulations, you were the first person to pre-order the new paperback…

View original post 354 more words

Advanced Review Copies of RUSSELL KIRK: AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE Now Available

If you’re interested in reviewing RUSSELL KIRK: AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE, please contact Mack McCormick at the University of Kentucky Press. Advanced review copies are now available.

If you’re interested in reviewing RUSSELL KIRK: AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE, please contact Mack McCormick at the University of Kentucky Press. Advanced review copies are now available.

Thank you, and enjoy!

New Contact Information, July 1, 2015

For those of you sending me physical reviews of books, CDs, etc., please note that my new mailing address (as of July 1, 2015) is:

Bradley Birzer/Stormfields

6 West Montgomery ST

Hillsdale MI 49242

USA

Bradbury and F451–Over at TIC

My thoughts on Bradbury and F451. Perfect Sunday afternoon reading–sans mechanical hounds.

http://www.theimaginativeconservative.org/2015/06/ray-bradbury-the-dystopia-of-fahrenheit-451.html

“The words are stones in my mouth”: Katatonia’s Sanctitude

A beautifully-conceived live album and concert video, Sanctitude finds Katatonia going (mostly) acoustic in a well-curated exhibition of songs sympathetic to the quieter spaces. Yes, there are candles, and yes, they play in a church, but this is not an overwrought episode of MTV Unplugged; rather it’s an essential expression for Katatonia and its songs, an approach they explored at length on their Dethroned and Uncrowned album, where they offered the entirety of Dead End Kings in similar stripped down fashion. Sanctitude is a complement to last year’s Last Fair Day Gone Night; where that live set, issued on CD/DVD last year, offered a rocked-out, straightforward career retrospective, the new album demonstrates why Katatonia is Katatonia. Because they’re a death metal, no a black metal, no a doom metal, no a shoe-gazey rock band — or are they? — that has the chops and the artistic will to…

A beautifully-conceived live album and concert video, Sanctitude finds Katatonia going (mostly) acoustic in a well-curated exhibition of songs sympathetic to the quieter spaces. Yes, there are candles, and yes, they play in a church, but this is not an overwrought episode of MTV Unplugged; rather it’s an essential expression for Katatonia and its songs, an approach they explored at length on their Dethroned and Uncrowned album, where they offered the entirety of Dead End Kings in similar stripped down fashion. Sanctitude is a complement to last year’s Last Fair Day Gone Night; where that live set, issued on CD/DVD last year, offered a rocked-out, straightforward career retrospective, the new album demonstrates why Katatonia is Katatonia. Because they’re a death metal, no a black metal, no a doom metal, no a shoe-gazey rock band — or are they? — that has the chops and the artistic will to…

View original post 581 more words

A Good Little Truth: BBT’s Wassail

Big Big Train, Wassail (English Electric, 2015)

Tracks: Wassail; Lost Rivers of London; Mudlarks; and Master James of St. George.

Wassail, the new EP from Big Big Train

Wassail, the new EP from Big Big Train

As far as I know, I’ve never tasted Wassail.

Of course, I come from Bavarian peasant stock and possess, sadly, not a drop of Anglo-Saxon or Celtic blood in my veins. My wife, however, is blessed with Celtic as well as Swedish ancestry, and I’m more than happy to have played a role in passing those genes on to our rather large gaggle of children.

As far back as I remember, though, my very German-American family drank something that sounds quite similar, at least in essence if not in accidents, to Wassail, Gluhwein. Even the very word Gluhwein conjures not just the scents of warm cinnamon, cloves, and anise, but also the idea of heavenly comfort and satiation.

Much the same could…

View original post 653 more words

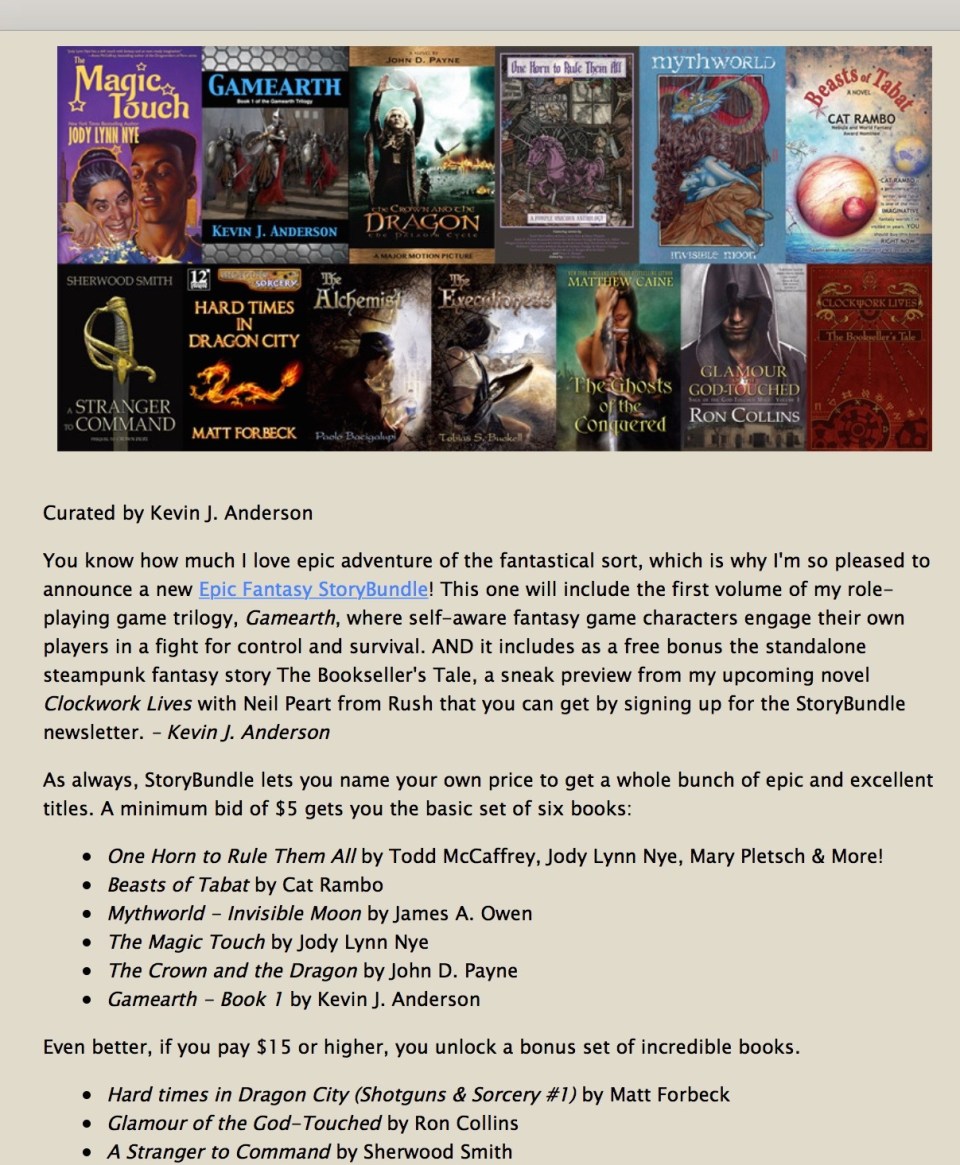

Fantasy Storybundle Featuring the Incomparable Kevin J. Anderson

If you’re interested (and you should be), go here: https://storybundle.com/fantasy